Fifty-three confirmed cases of a highly pathogenic and deadly strain of bird flu have been found in wild birds in North Carolina.

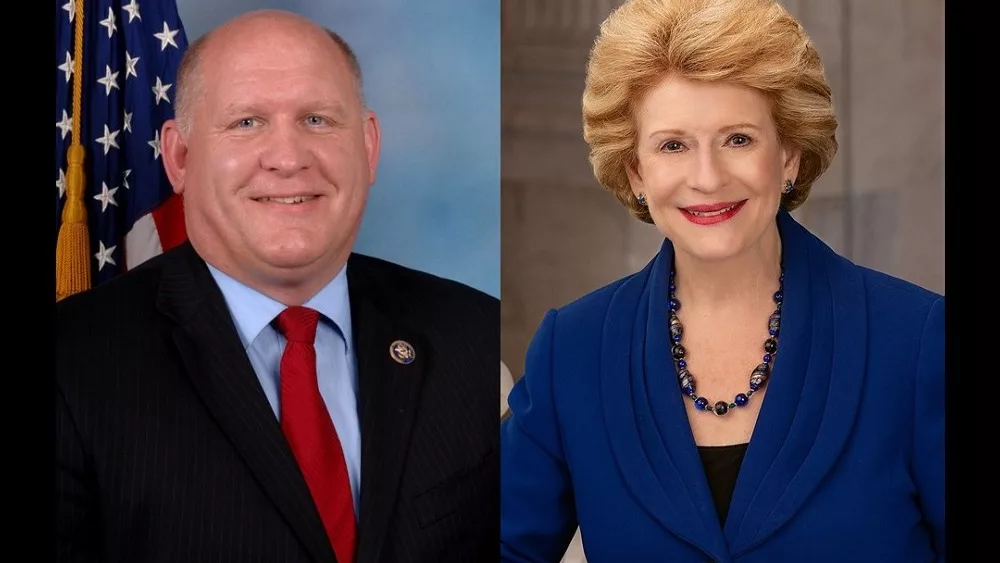

According to Dr. Zac Williams, poultry specialist at Michigan State University and board member of the Michigan Allied Poultry Industries, no one knows how it came to the U.S.

“There is a risk it could transfer from the wild birds into our domestic poultry—that’s what happened during the 2014-2015 outbreak,” he says.

Producers can reduce those risks with some basic biosecurity measures.

“Limiting visitors to farms; only necessary personnel or employees; having the correct personal protective gear like boot covers, coveralls and hairnets,” says Williams. “Things like that to separate the outside world from the farms and make sure we’re not carrying anything inadvertently to these farms. No contact with wild birds, no contact with any outside poultry.”

Williams says the greatest risk for it to make it to Michigan is when ducks and geese migrate back to Canada and northern areas this spring.

“When they fly back, it’s getting warmer, the days are longer, and they go over to their summering grounds which are further north,” he says. “Usually our highest risk or chance of an outbreak is in the spring when the ducks are migrating back north.”

With the 2015/2015 outbreak still fresh in producers’ minds, Williams says producers have a more heightened sense of security.

“Our farmers know what’s happening—they’re well-prepared. We have an annual biosecurity training for them. We’ve gone over workshops and ran through scenarios. Just practice good biosecurity measures.”